Representing the First Non-Military settlement in Southeastern

Colorado, Boggsville was established on the Banks of the Purgatoire River, near its confluence with the

Arkansas River, in 1866. When

New Mexico Territory was added to the United States, the lands south of the Arkansas River were opened to homesteaders and the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail in Colorado shifted from trading to ranching and agriculture.

For years

Bent's Old Fort had been the center of trade for this large area. However, by the time the Mexican-American War began in 1846 the U.S. Army decided to use the post as a staging base for the conquest of New Mexico. That summer General Stephen W. Kearny and his Army of the West, consisting of about 1,650 dragoons and

Missouri Volunteers from

Fort Leavenworth,

Kansas, followed by some 300 to 400 wagons of Santa Fe traders, rested at the fort before proceeding to occupy New Mexico. After the war the Government failed to adequately compensate the Bents for their use of the fort and business began to decline due to unrest among the southern Indian tribes and raids against the wagon trains. In 1849,

William Bent offered to sell the fort to the U.S. Army in 1849, but they declined. Disillusioned, he set fire to the fort and moved 38 miles down the

Arkansas River, where he founded Bent's New Fort in an ill-fated attempt to restore his trading business. In 1859 William Bent leased his new fort to the Army.

Not only did the final closing of Bents Fort create a loss for travelers along the

Santa Fe Trail, it also created a loss of jobs for a number of men, one whom was a man named Thomas Boggs. Thomas had worked for the Bents since about 1843 raising and maintaining livestock between Taos, New Mexico and the mouth of the Purgatoire River. Boggs married Ramalda Luna, the stepdaughter of Charles Bent, in Taos in 1846. She was also related by marriage to the

Kit Carson and was an heir to Cornelio Vigil, who along with

Ceran St. Vrain, owned a 2,040 acre land grant. After having spent time in

California in the 1850's, he returned to the area and worked for

Lucian Maxwell and Kit Carson up to about 1862. Moving to Rayado, New Mexico, he ran cattle to the lush bottomlands on the mouth of the Purgatoire River near present-day Las Animas, Colorado.

Having acquired land through his well-connected wife, Rumalda, Thomas moved his family to present-day Colorado in 1862. There, they built an L-shaped, 6-room home on the west bank of the Purgatoire River. The same year he also built a trading store that would service the area as well as travelers along the Santa Fe Trail. Before long, more settlers moved to the area and the ranching and agricultural settlement of Boggsville was born. Just a few years later, with the help of some of the locals, Boggs built a larger adobe house in 1866 that Territorial architecture with Spanish Colonial architecture.

In 1867, more residents arrived at Boggsville when

Fort Lyon moved to a new site just three miles northeast of town. Before long, Boggsville developed the first large-scale farming and ranching operations in southeastern Colorado, which included irrigation. That year residents dug an irrigation canal called the Tarbox Ditch, which was seven miles long and irrigated more than 1,000 acres. Fort Lyon would buy nearly everything the farmers at Boggsville could produce. During this period Boggsville grew from a few adobe structures to a full-fledged community of 20 or more buildings

.

One of most influential people to arrive in Boggsville that year was a merchant and rancher by the name of John W. Prowers and his

Cheyenne wife named Amache. Prowers had also been a teamster who had worked for William Bent and for the Sutler at Old Fort Lyon. Planning on doing business with Fort Lyon, he built a large two-story, U-shaped adobe house with 14 rooms. Not only did it serve as the family's living quarters, but at various times as a town center, stagecoach station, school, and political office. In addition, Prowers built a general store on the east side of Boggsville which opened when brother-in-law, John Hough, arrived with merchandise later in the year. The store sold cloth, candles, knives, saddles, powder and shot, boot, liquor, beef from Prowers' Hereford cattle and other general groceries. Prowers raised horses, cattle, and sheep eventually growing his cattle herd to some 10,000 head by the 1880s.

Also arriving was none other than Kit Carson, who settled in Boggsville in December, 1867. It would be his final home. Early in 1868, Carson traveled to Washington, DC, to help negotiate a treaty with the Ute Indians. Soon after his return, his wife Josefa died on April 23, 1868 from complications after giving birth to their eighth child. When Carson had arrived home he had been feeling ill and it worsened after the death of his wife. He was soon moved to Fort Lyon, where he died on May 23, 1868. His body was brought back to Boggsville and buried next to his wife, who had died a month earlier. Their bodies were later reinterred in Taos for permanent burial. Boggs was named the executor of Carson’s will, and the Carson children became part of Boggs’s extended family.

By 1870, Boggsville had become the center of society in the area and was named the county seat. Thomas Boggs became the town’s first sheriff in 1870, and he was elected to the territorial legislature the following year. The county offices were located in the Prowers House and a public school was built. In a short time the settlement of Boggsville grew into a center for trade and education

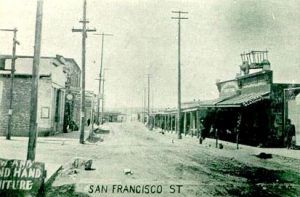

As the area developed a new town sprang up across the Arkansas River in February, 1869 called Las Animas City and a bridge was built across the river. In the beginning Las Animas City was a rough and tumble town and no threat to Boggsville. That would change however, when the the Kansas Pacific Railroad built a branch line from Kit Carson to Fort Lyon in 1873 and built its own town, which they called West Las Animas. The same year, Boggsville lost its county seat status to Los Animas City. John Prowers also relocated to Las Animas, where he built a new house and opened a general store. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad arrived in Las Animas two years later. Thomas Boggs moved to Springer, New Mexico in 1877 after his wife's land grants were contested.

By 1880 the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad had reached Santa Fe, New Mexico, hammering a death knell in the use of the Santa Fe Trail. Now freight could be transported by rail car and there was no need for wagon caravans across the plains. This was the final blow for Boggsville. In 1883, after Boggs' ownership of the land was confirmed, he sold the property to a man named John Lee for $1,200. It later became the San Patricio Ranch of 3,000 acres under the Lee family. Afterwards it began to pass through a number of hands; however both the Prowers and Boggs homes remained intact.

In 1985 the owners donated 110 acres encompassing the Boggsville site to the Pioneer Historical Society of Bent County. Using a grant from the State Historical Fund, the Pioneer Historical Society restored the Boggs and Prowers Houses over the next decade and opened them to the public as an interpretive museum. Boggsville was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 24, 1986. Boggsville is located on the Purgatoire River, two miles south of present day Las Animas on Colorado Highway 101. It is open during the spring and summer months.