Kansas is home to many ghost towns, remnants of a time when the state was a frontier outpost. These towns were once bustling communities, but they have since been abandoned due to factors such as economic decline, natural disasters, and changes in transportation routes. Today, these ghost towns offer a glimpse into the past, with their crumbling buildings and deserted streets serving as reminders of a bygone era.

Here are some of the most notable ghost towns in Kansas:

Alcove, Marshall County – Now a well-preserved park. This was never an official town but was a stop on the Oregon Trail. Numerous carvings in the spring’s rocks feature travelers’ initials and other things. A member of the Donner Party is buried nearby.

Amy, Lane County – Post Office 1887-1954 – Only a grain elevator, an old school, and agricultural buildings remain.

Arrington, Atchison County – Post Office 1879-1973 – Today, were it not for the sign indicating the town and the few scattered homes about, it would be difficult to know that a town had ever existed. It is located about 26 miles southwest of Atchison on Kansas Highway 119.

Arvonia, Osage County – Post Office 1869-1901 – Arvoinia is still called home to a historic one-room school, an old church, and a few area homes.

Asherville, Mitchell County – Post Office 1869-1980 – A small population still exists.

Auburndale, Shawnee County – Post Office 1888-1899 – Auburndale is currently a neighborhood in Topeka and is commemorated by Auburndale Park.

Aulne, Marion County – Post Office 1887-1954 – Located in Wilson Township, it was a station on the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad six miles south of Marion. Today, the town still has a few buildings and an active church.

Bala, Riley County – Post Office 1870-1966 – Fort Riley has expanded into much of the area where Bala once stood. Today, there is very little left of Bala except for a few hardscrabble houses and the old deteriorating Presbyterian Church.

Barnard, Lincoln County – Post Office 1888-present – Though there are a few remaining businesses today, and the post office is still in operation, the population of this once prosperous community has dropped to just about 63 people.

Bavaria/Honek, Saline County – Post Office 1867-1986 – First called Honek, the name changed to Bavaria in 1880. Though located on the mainline of the Union Pacific Railroad, Bavaria did not grow. By 1910, its population had dropped to 110. Today, just a handful of people live in the old town, where several buildings sit abandoned and deteriorating in the elements.

Bazaar, Chase County – Post Office 1860-1874. One of the county’s oldest towns, the settlement started in March 1856. Bazaar peaked in about 1921, with a population of 100. That year, it was the largest railroad cattle shipping point in the state, hauling about 1,800 to 2,000 cars of stock annually. Today, it has a historic school, a still-active Methodist Church, and a few scattered homes.

Beaumont, Butler County – Post Office 1880-1997 – An unincorporated community and semi-ghost town in Glencoe Township. Several area homes, vacant business buildings, and a population of about 30.

Beaver, Barton County – Post Office 1919-1992 – A small population remains.

Belvidere/Glick, Kiowa County – Post Office 1883-1996 – Originally founded as Glick, the name changed to Belvidere in 1890. A small population remains.

Bendena, Doniphan County – Post Office 1886-present – A small community remains along K-20.

Big Springs, Douglas County – Post Office 1856-1903 -A small population remains along U.S. 40.

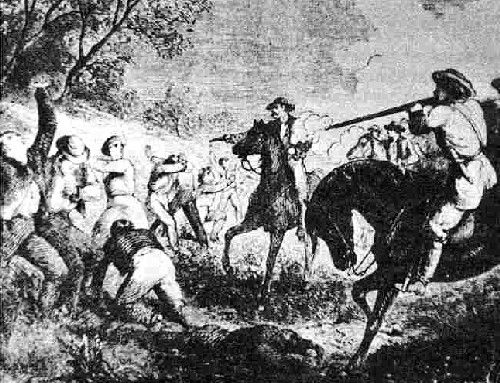

Blackjack, Douglas County – Post Office 1858-1895 – Santa Fe Trail wagon swales, a roadside park, cemetery, and the well-preserved battlefield site remain open to the public.

Black Wolf, Ellsworth County – Post Office 1879-1953 – A grain elevator and other buildings remain. Black Wolf is currently on private property.

Blaine, Pottawatomie County – Post Office 1874-1976 – St. Columbkille Catholic Church and former Catholic School still stand at the intersection of K-99 and K-16.

Blakeman, Rawlins County – Post Office 1887-1952 – Little remains of the townsite.

Bloom, Ford County – Post Office 1885-1891 & 1908-1992 – Several buildings and a few residents, but no open businesses.

Bluff City, Harper County – Post Office 1887-present – 2008 estimated population of 73. Bluff City was initially founded as a fraud in 1873 to swindle money from the Kansas legislature. The first settlers in the area didn’t arrive until 1876.

Boyd/Maherville, Barton County – Post Office 1874-1937 – Some abandoned buildings and ruins remain. Known initially as Maherville. The name changed to Boyd in 1904.

Brookville, Saline County – Post Office 1870-present – 2010 population of 262. The population was once near 2,000 in the 1870s, but the population began to decline after the turn of the century.

Burdick, Morris County – Post Office 1887-present – A very small population and a few buildings.

Bushong, Lyon County – Post Office 1887-1976. The small town has an estimated population of about 30. Several ruins of the downtown and old consolidated school remain.

Byers, Pratt County – Post Office 1915-present. The small town has an estimated population of 33.

Cadmus, Linn County – A ghost town located in the north-central part of Linn County on Elm Creek. It got its start as an agricultural community.

Calista, Kingman County – Post Office 1886-1896 & 1902-1955 – An old grain elevator and a couple of houses remain.

Canada, Marion County – Post Office 1884-1954 – A small population of approximately 40 remains.

Carlton, Dickinson County – Post office 1872-1995 – Once a busy station and shipping point on the Kansas Pacific Railroad. As of the 2020 census, its population was 40.

Carneiro, Ellsworth County – Post Office 1882-1953 – A small population remains north of Mushroom Rock State Park.

Castleton, Reno County – Post Office 1872-1957 – A few homes and abandoned buildings remain. Castleton was used as the setting of Sevillinois for the 1952 movie Wait Till the Sun Shines, Nellie.

Cato, Crawford County – Post Office 1858-1905 – The Cato Historical Preservation Association meets at 6:30 pm on the fourth Tuesday of each month at Arcadia Community Center, Arcadia, Kansas. The old school has been restored. Cato Christian Church is in good repair but closed. A community reunion is held yearly.|

Cedar Point, Chase County – Post Office 1862-Present – Today, it is a semi-ghost town with several remaining buildings and a historic flour mill.

Centropolis, Franklin County – Post Office 1854-1930 – A small population remains on a county road about ten miles northwest of Ottawa. The Christian Church and Baptist Church remain open.

Clayton, Norton County – Post office 1879-19?? – Semi-ghost town located primarily in Norton County but also in Decatur County. Building ruins and a small population remain.

Clements, Chase County – Post office 1884-1988 – First called Crawfordsville. Little remains except for a beautiful stone arch bridge, ruins, a couple of old buildings, and an old store.

Coolidge, Hamilton County – Post Office 1873-1875 & 1881-present – 2008 estimated population of 86. The original town was called Sargent but it changed to Coolidge in 1881.

Croft, Pratt County – Post Office 1907-1961 – Two vacant grain elevators, two vacant houses, an old school, and a few ruins remain in this town.

Croweburg, Crawford County – Post Office 1908-1972 – A small population remains with some shotgun houses and some building ruins.

Defiance, Woodson County – Post Office 1873-1886 – Only a hotel remains used as a residence.

Delavan, Morris County – Post Office 1886-1992 – A few area people, old school, community center.

Denmark, Lincoln County – Post Office 1872-1904, 1917-1954 – One of the first permanent settlements in Lincoln County, it was settled about 1869 by Danish Lutherans who laid the cornerstone for a stone church in 1876. The church and several other buildings still stand.

Dubuque, Russell & Barton Counties – Post Office 1879-1909 – A beautiful Catholic church and cemetery are all that remain.

Diamond Springs, Morris County – Post Office 1825-1863 – A Santa Fe Trail stop. Few remains exist, but a monument to Diamond Springs was erected in Diamond Springs Cemetery.

Dispatch, Smith County – Post Office 1891-1904 – A church, some houses, and a cemetery remain.

Doniphan, Doniphan County – Post Office 1854-1943 – Still on maps but little remains. A trading post was established on the site in 1852.

Dunlap, Morris County – Post Office 1874-1988 – Estimated population of 27.

Drury, Sumner County – Post Office 1884-1921 – A small population (approx. 20) remains, along with a dam built in 1882.

Dry Creek, Saline County – Post Office 1877-1887 – An old blacksmith shop still stands, but nothing else remains.

Eagle Springs, Doniphan County – Post Office 1883-?? – The townsite was abandoned, and only ruins remain. It was a health resort that lasted into the 1930s.

Elgin, Chautauqua County – Post Office 1871-1976 – 2008 estimated population of 71. Also known as New Elgin.

Elk Falls, Elk County – Post Office 1870-present – A small town of about 100 now, home of the annual “Outhouse Tour,” claimed to be Outhouse Capital and home of historic Elk Falls Bridge.

Elmo, Dickinson County – Post Office 1866-1966 – A few buildings and a small population remain.

Empire City, Cherokee County – Post Office 1877-1907 – Several buildings and a small population. Empire City was annexed to Galena, Kansas, in 1907.

Englewood, Clark County – Post Office 1885-present – Estimated population of 69.

Fairport, Russell County – Post Office 1881-1959 – A small population remains.

Farlington, Crawford County – Post Office 1870-present – A small population remains in the area. Farlington is located just southwest of Crawford State Park on K-7.

Franklin, Douglas County – Post Office 1853-1867 – An early stage stop near Lawrence, Kansas. Nothing remains of the town except two small neglected cemeteries and Franklin Road off of K-10.

Freeport, Harper County – Post Office 1885-present – With a population of just about four people, Freeport was the smallest incorporated town in Kansas until November 2017, when a vote of 4–0 dissolved the city. It still supports a church, a grain elevator, and a post office.

Frederick, Rice County -Post Office 1887-1954 – Frederick is the smallest incorporated town in Kansas and today has just a population of about 18.

Fulton, Bourbon County – Post Office 1869-1998. The town was established in 1869 near the site of old Fort Lincoln. Fulton’s population peaked in 1890 at 506 and dropped afterward. It still has several old business buildings, including a school and gymnasium. It is still called home to about 112 people.

Galatia, Barton County – Post Office 1889-1966 – 2020 estimated population of 36.

Gem, Thomas County – Post Office 1885-2014 – Semi ghost town, no open business, but retains a small population and several homes.

Granada/Pleasant Spring, Nemaha County – Post Office 1856-1906 – Some ruins and abandoned buildings remain on what used to be Main Street. Originally known as Pleasant Spring. Changed to Granada in 1864.

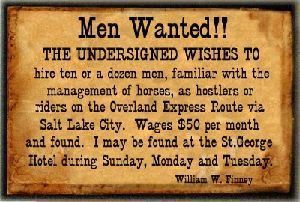

Guittard Station, Marshall County – Post Office 1861-1900 – Some abandoned buildings remain. Guittard Station was a major stop for the Pony Express.

Harlan/Thompson, Smith County – Post Office 1873-1995 – A small population remains as well as the ruins of Main Street and a high school gymnasium. Harlan was home to Gould College, which lasted from 1881 until 1891. The settlement was first named Thompson but was changed to Harlan in 1877.

Havana, Osage County – Post Office 1858-Early 1870s – Ruins of the Havana Stage Station and hotel remain, and a sign has been posted on the site. Not to be confused with Havana in Montgomery County.

Hawkeye, Decatur County – Post Office 1879-1896 – Little remains of the townsite.

Heizer, Barton County – Post office 1891-1954. Several homes and a small population remains.

Hewins, Chautauqua County – Post Office 1887-1966 – A small population remains.

Hitschmann, Barton County – No post office. Some old buildings remain. All of Hitschmann is currently on private property.

Holland, Dickinson County – Post Office 1872-1875 & 1884-1906 – A church, now used as a town hall and a few houses, remain.

Hopewell/Fravel, Pratt County – Post Office 1904-1908 & 1916-1973 – A small population (approx. 10) remains. The name changed to Fravel in 1916 but changed back to Hopewell in 1921.

Horace, Greeley County – A semi-ghost town in central Greeley County. Its post office lasted from 1886 to 1965. Though the nearby town of Tribune tried to annex Horace in 2007, Horace citizens decided against consolidation. The City of Horace maintains a separate city council to manage its affairs. Today, Horace is home to only about 65 people with no open retail businesses.

Hunnewell, Sumner County – Post Office 1880-1960 – 2020 estimated population of 64. In the 1880s, Hunnewell flourished as a busy shipping point for Texas cattle and, like other Kansas Cowtowns, had a bawdy reputation for a time.

Huron, Atchison County – Post Office 1882-1992 – Several remaining homes and buildings. 2010 population of 54. Located about 17 miles northwest of Atchison on U.S. Highway 73.

Hunter, Mitchell County – Post Office 1895-present – Semi-ghost town with a population of 57. It still retains its post office and just a few businesses.

Industry, Dickinson & Clay County – Post Office 1876-1906 – A small population of fewer than 20 remains.

Irving, Marshall County – Post Office 1859-1960 – Located on Corps land and is easily accessible. Abandoned for the construction of Tuttle Creek Lake.

Jerome, Gove County – Post Office 1886-1943 – Little remains of the townsite.

Kackley, Republic County – Post Office 1888-1968. It started as a station on the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad and did well until the early 1900s. Its population peaked in 1910 at about 250 and fell afterward.

Kanona, Decatur County – Post Office 1887-1955 – Some ruins and abandoned buildings remain. The site of Kanona is currently on private property.

Kendall/Zamora, Hamilton County – Post Office 1879-present – A small population remains. Originally called Zamora when a post office opened in 1879. It was changed to Kendall in 1885.

Kickapoo City, Leavenworth County – Post Office 1854-1920 – A small population remains in the area.

Kingsdown, Ford County – Post Office 1888-1891, 1892-1893 & 1904-1998 – Several remaining homes & buildings. A small population remains in the area.

Kipp, Saline County – Post Office 1890-1957 – A small population remains.

Lake City, Barber County – Post Office 1873-1993 – A small population (approx. 30) remains. The United Methodist Church is open.

Latimer, Morris County – Post Office 1887-1961 – A small population of about 20 people. The Lutheran Church remains open.

LeHunt, Montgomery County – Post Office 1905-Early 1930s – Some ruins remain east of Elk City Lake. The town was bustling thanks to a central cement factory in the center of town being the biggest employer. During the Great Depression, cement sales dropped significantly, and the company went out of business, so the town died.

Lone Elm, Anderson County – Post Office 1879-1956. Located in Lone Elm Township of southeast Anderson County, it is officially an extinct town because it no longer has a post office. However, as of the 2020 census, its population was 27.

Lone Star, Douglas County – Post Office 1899-1953 – A small population remains just south of Clinton Lake near Lone Star Lake. A community existed in the area before Lone Star was organized. A post office was formed in 1875 under the name of Bond, then Gideon. The name Lone Star was chosen in the 1890s.

Ludell, Rawlins County – Post Office 1881-present – A small resident population remains along with some ruins and abandoned buildings.

Lyona, Dickinson County – Post Office 1869-1888 – Nothing remains of the townsite except for a church & the old Lyona School built in 1870.

Marietta, Marshall County – Post Office 1890-1959 – A small population and a few buildings remain.

McAllaster, Logan County – Post Office 1887-1897, 1903-1903 & 1906-1953 – A small population exists, and several buildings remain.

Medora, Reno County – Post Office 1887-1988 – Little remains of the townsite except for a small population.

Midian, Butler County – Post Office 1916-1950 – The townsite is now on private property.

Mildred, Allen County – Post Office 1907-1973 – 2020 estimated population of 25.

Millbrook, Graham County – Post Office 1878-1889 – The ruins of a schoolhouse remain in the area.

Miller, Lyon County – Post Office 1887-1905 & 1912-1958 – A small population and some abandoned businesses remain in the area.

Monmouth, Crawford County – Post Office 1857-1955 – Very little remains of the townsite.

Monticello, Johnson County – Post Office 1857-1905 – The old schoolhouse, cemetery, and a few houses from the 1940s remain south of Shawnee Mission Parkway in west Shawnee and Lenexa.

Monument, Logan County – Post Office 1880-1997 – Though Monument is officially an extinct town today, the railroad still runs through the town and the grain elevators still operate serving area farmers. Throughout the community are numerous old buildings and homes in various states of disrepair.

Morton City, Hodgeman County – Post Office 1877-1880s – Some ruins of old stone houses remain. The townsite is now a part of the Hanna Hereford Ranch.

Muscota, Atchison County – Post Office 1861-present – Like other small Kansas towns, Muscotah declined in the 20th century. Though it still maintains a post office and about 167 people, the village is filled with abandoned buildings. It is located about 26 miles west of Atchison on U.S. Highway 159.

Nekoma,Rush County –Post Office 1960-2008. A few remaining buildings and residents.

Neosho Falls, Woodson County – Post Office 1857-present – 2020 estimated population of 137.

Neuchatel, Nemaha County – Post Office 1864-1901 – The cemetery, church, town hall, and schoolhouse have all been restored and well-kept.

Newbury, Wabaunsee County – Post Office 1870-1888 – A small population and a large Catholic church remain three miles north of Paxico.

Nicodemus, Graham County – Post Office 1877-1918 & 1920-1953 – See full article about this black pioneer town here. National Historic site.

Oil Hill, Butler County – Post Office 1918-1969 – The townsite is on private property, but the Kansas Turnpike does pass under Oil Hill Road just outside of El Dorado.

Ottumwa, Coffey County – Post Office 1857-1906 – A small population remains on the north edge of the John Redmond Reservoir.

Palermo, Doniphan County – Post Office 1855-1904 – A small population remains eight miles southeast of Troy near the Missouri River.

Parkerville, Morris County – Post Office 1892-1953 – A population of about 60. Only the Baptist Church remains open.

Pawnee, Riley County – Post Office 1854-1855 – The old territorial capitol building still stands is well-preserved. Was the territorial capital until 1855 when it was moved to Shawnee Mission.

Peoria, Franklin County – Post Office 1857-1934 – A small population remains, and Peoria Township is named for it.

Peterton, Osage County – Post Office 1876-1904 – There is still a small population in the area.

Pfeifer, Ellis County – Post Office 1887-present – Home to the beautiful Holy Cross Church, voted as one of the 8 Wonders of Kansas Architecture, and only about 80 people.

Pierceville, Finney County – Post Office 1873-1874 & 1878-1992 – A small population remains along U.S. 50.

Potter, Atchison County – Post Office 1888-present – Like so many other flourishing agricultural and railroad towns that flourished a century ago, Potter declined over the years. The town is unincorporated today and very small, but it still maintains a post office and one open business.

Potwin Place, Shawnee County – Post Office 1869-1899 – The site is well-preserved off of SW 6th Avenue in Topeka and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Potwin was annexed to Topeka in 1899.

Prairie City, Douglas County – Post Office 1857-1883 – A cemetery, ruins of an old church, and an abandoned stone house are all that remain of the town.

Ransomville, Franklin County – Post Office 1878-1914 -The Ransom house still stands, as do some other houses and buildings.

Quindaro, Wyandotte County – Post Office 1857-1909 & 1921-1954 – Some remains of Quindaro are now in the city limits of Kansas City in Quindaro Park.

Ravanna, Finney County – Post Office 1882-1922 – Only foundations remain. Battled with Eminence for the county seat of Garfield County. In 1893, Garfield County was annexed to Finney County, and the feud was over.

Raymond, Rice County – Post Office 1872-? – Estimated population of 76 in 2020.

Reamsville/Beaver, Smith County – Post Office 1878-1941 – A small population remains. An Old Dutch Mill, built in 1882, was moved to Smith Center in 1938. Originally called Beaver. The name changed to Reamsville in 1882.

Richland, Shawnee County – Post Office 1857-1960s – Nothing remains of the townsite except some ruins and the cemetery.

Rollin, Neosho County – Post Office 1890-1921 – Nothing remains of the townsite except Delos Johnson’s (the town founder) house and a neglected cemetery.

Rosalia, Butler County – Post Office 1870-present – A small population (approximately 100) still exists.

Roxbury, McPherson County – Post Office 1872-present – A small population of about 70 remains in the area.

Russell Springs, Logan County – Post Office 1887-1997 – Though Russell Springs, Kansas, is a semi-ghost town today, it served as the Logan County seat for 76 years before losing the seat to Oakley. It had a population of about 24 in 2020.

Saxman, Rice County -Post Office 1891-1952 – A small population (approx. 30) remains.

Shields, Lane County – Post Office 1887-1994 – A small population and numerous buildings remain, but no open businesses.

Sidney, Ness County – Post Office 1877-1888 – Only foundations remain.

Silkville, Franklin County – Post Office 1870-1892 – Several buildings remain, including an old house and a stone school southwest of Williamsburg.

Sitka, Clark County – Post Office 1909-1964 – A small population and some abandoned buildings and ruins still remain.

Skiddy/Camden, Morris County – Post Office – 1869-1953 – A small population (approx. 20) remains in the area. In 1879, the town’s name was changed to Camden, and in 1883, it was changed back to Skiddy.

Smileyberg, Butler County – Post Office 1904-Early 1920s – Some structures still remain. A transmission shop is open.

Springdale, Leavenworth County – Post Office 1860-1907 – The Kansas City Metro area has grown into the area of Springdale.

Stanton, Miami County – Post Office 1857-1903 – Several houses and businesses remain. William Quantrill lived in Stanton during the winter of 1859-60.

Stull, Douglas County – Post Office 1899-1903 – Just a few homes and a cemetery. Originally called Deer Creek until 1899, when the post office opened.

Sun City, Barber County – Post Office 1873-1894 & 1909-present – 2020 estimated population of 48.

Sunflower/Clearview City, Johnson County – Post Office 1943-1958 – Old residences, streets, and other buildings remain in and around Clearview City. Sunflower Village was established exclusively for the Sunflower Army Ammunition Plant, the plant and town remain just off of K-10 south of DeSoto.

Talmo, Republican County – An unincorporated ghost town in Republic County. It still has a few homes and a couple of business buildings.

Trading Post, Linn County – Trading Post, Kansas, the first permanent white settlement in Linn County and one of the first in the state, is situated on the Marais des Cygnes River. Though filled with history, the community is a ghost town today.

Vesper, Lincoln County – Post Office – 1872-1966 – It still has a small population and a few old homes and buildings.

Vinland, Douglas County – Post Office 1868-1954. An early settlement of Douglas County, Kansas, Vinland is situated along the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad about seven miles south of Lawrence. The town has a very small population today.

Vliets, Marshall County – Vliets as officially platted and laid out in 1889 along the Central Branch Railroad and the Vermillion River. Once supporting as many as 350 people, all that is left today is a Co-op Elevator. Post Office 1887-1992.

Waterloo, Kingman County – Post Office 1878-1912. Though it is officially an “extinct” town because it no longer has a post office, it still displays several homes, buildings, and a small population.

Wheeler, Cheyenne County – Wheeler started when the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad came through. Post office 1888-1988.

Willis, Brown County – In Mission Township of Brown County. Though it showed much promise in its early days, it is a shell of its former self today. Today, Willis still displays a couple of old business buildings, homes, a grain elevator, and several silos. The former high school is in a state of decay and has crumbled in on itself. The area is still called home to about 35 people.

Winifred, Marshall County – The town of Winifred was founded in 1907 and flourished in its early years but it has only a few buildings left today. Post Office 1858-1986.

Zeandale, Riley County – Established in 1854 near Manhattan, this farming community never grew very large. Post Office dates 1857-1944. Still has several homes and an active church.

Zenith, Stafford County – Post Office 1902-1974 – A small population of about 20 remains.