Five miles northeast of Hanover, Kansas is the only remaining Pony Express stop still standing in its original location. Built on Cottonwood Creek in 1857 by Gerat H. Hollenberg, this station was also the largest stop along the Pony Express route. Intending to capitalize on the many wagon trains passing his way on the Oregon-California Trail, Hollenberg’s six-room building initially served as a grocery store, tavern, and an unofficial post office. Three years later it became a Pony Express station and later a stagecoach station.

The Pony Express Route, which ran 2,000 miles from St Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, California was in operation for only 18 months, from April 1860 through October 1861. Amazingly, these young riders carried approximately 35,000 pieces of mail over more than 650,000 miles during this time and it is said they only lost one sack of mail during this time.

Before the Pony Express, the railroads and telegraph lines extended no further west than St. Joseph, Missouri and mail traveled west by stagecoach and wagons, a trip that could take months if it arrived at all. The Pony Express alleviated this problem with riders who could dramatically reduce the amount of time it took for the mail to be delivered. But, it was a dangerous job, fraught with Indian attacks, rough terrain and severe weather.

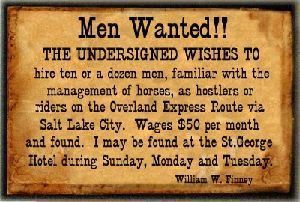

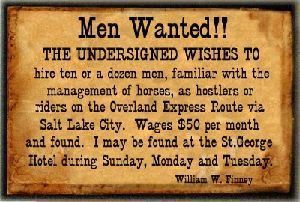

Pony Express Want Ad

For this reason, a Pony Express an 1860 advertisement in California read: “Wanted. Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over 18. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred.” Most of the riders were around 20, but there was one that was only 11 and the oldest rider was in his mid-40’s. Usually, they weighed about 120 pounds. One Hundred, eighty-three men rode for the Pony Express, each receiving $100 per month in pay. Riding in a relay fashion, each rider would cover about 75-100 miles before another rider took his place on the route. However, riders received fresh horses every 10-15 miles. The entire one-way trip would take about ten days.

While the Pony Express dramatically improved the communication between the east and west, it was a financial disaster for its owners. Hoping to gain a million-dollar government mail contract, the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company spent about $700,000 on the project, losing about $200,000 of their investment. The owners failed to gain the million-dollar contract and when the telegraph was completed in October 1861, the company declared bankruptcy and closed down.

Afterward, most of the 163 stations fell into ruins but somehow the Hollenberg Station managed to survive. In 1869, the town of Hanover was founded and its residents made every effort to preserve the old station. The building is now located on a state historical park and operates as a museum and visitor’s center.

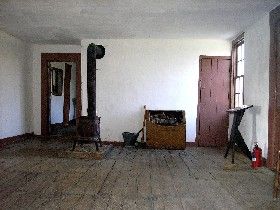

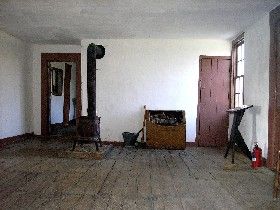

Hollenberg Station Interior

However, according to many visitors and staff members, some Pony Express riders have chosen to linger at the station long after the building ceased to serve the Pony Express. Many claim to have heard the sounds of pounding hoofs thundering through the night and the distant sounds of young men calling out as their phantom mounts near the station. Others have even claimed to have seen the riders. Witnesses also report the occurrence of many strange sounds and cold spots within the building.

Hollenberg Station is located four miles north of U.S. 36 on K-148, and one mile east on K-243 in Hanover, Kansas. Open seasonally.

The Pony Express Route, which ran 2,000 miles from St Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, California was in operation for only 18 months, from April 1860 through October 1861. Amazingly, these young riders carried approximately 35,000 pieces of mail over more than 650,000 miles during this time and it is said they only lost one sack of mail during this time.

Before the Pony Express, the railroads and telegraph lines extended no further west than St. Joseph, Missouri and mail traveled west by stagecoach and wagons, a trip that could take months if it arrived at all. The Pony Express alleviated this problem with riders who could dramatically reduce the amount of time it took for the mail to be delivered. But, it was a dangerous job, fraught with Indian attacks, rough terrain and severe weather.

Pony Express Want Ad

For this reason, a Pony Express an 1860 advertisement in California read: “Wanted. Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over 18. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred.” Most of the riders were around 20, but there was one that was only 11 and the oldest rider was in his mid-40’s. Usually, they weighed about 120 pounds. One Hundred, eighty-three men rode for the Pony Express, each receiving $100 per month in pay. Riding in a relay fashion, each rider would cover about 75-100 miles before another rider took his place on the route. However, riders received fresh horses every 10-15 miles. The entire one-way trip would take about ten days.

While the Pony Express dramatically improved the communication between the east and west, it was a financial disaster for its owners. Hoping to gain a million-dollar government mail contract, the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company spent about $700,000 on the project, losing about $200,000 of their investment. The owners failed to gain the million-dollar contract and when the telegraph was completed in October 1861, the company declared bankruptcy and closed down.

Afterward, most of the 163 stations fell into ruins but somehow the Hollenberg Station managed to survive. In 1869, the town of Hanover was founded and its residents made every effort to preserve the old station. The building is now located on a state historical park and operates as a museum and visitor’s center.

Hollenberg Station Interior

However, according to many visitors and staff members, some Pony Express riders have chosen to linger at the station long after the building ceased to serve the Pony Express. Many claim to have heard the sounds of pounding hoofs thundering through the night and the distant sounds of young men calling out as their phantom mounts near the station. Others have even claimed to have seen the riders. Witnesses also report the occurrence of many strange sounds and cold spots within the building.

Hollenberg Station is located four miles north of U.S. 36 on K-148, and one mile east on K-243 in Hanover, Kansas. Open seasonally.