The site of Fort Riley, Kansas was chosen by surveyors in the fall of 1852 and was first called Camp Center, due to its proximity to the geographical center of the United States. The following spring, three companies of the 6th infantry began the construction of temporary quarters at the camp.

On June 27, 1853, the camp’s name was changed to Fort Riley in honor of Major General Bennett C. Riley, who had led the first military escort along the Santa Fe Trail and had died earlier in the month.

The fort’s initial purpose was to protect the many pioneers and traders who were moving along the Oregon-California and Santa Fe Trails.

The First Territorial Capitol at Pawnee, Kansas was only used for one session, before moving to Lecompton, Kansas when the pro-slavery advocates were in control of the state. Photo by Kathy Weiser-Alexander.

Many of the buildings at the fort were built with the native limestone of the area, several of which continue to stand today. By 1855, the post was well-established and as more and more people moved westward, additional quarters, stables and administrative buildings were authorized to be built. In July, 56 mule teams arrived at the fort, loaded with materials and soldiers to expand the fort.

However, just a few short weeks later, cholera broke out among the fort and though the epidemic lasted only a few days, it left in its wake some 75-125 people dead.

As tensions and bloodshed increased between the pro and anti-slavery settlers, resulting in what has become known as “Bleeding Kansas,” Fort Riley’s troops took on the additional task of “policing” the troubled territory while continuing to patrol the Santa Fe Trail as Indian attacks increased.

When the Civil War broke out, the vast majority of the troops stationed at Fort Riley were sent eastward. However, some soldiers were left to continue to guard those traveling west and the base was utilized as a prisoner of war camp for captured Confederates. After the Civil War, troops from Fort Riley were needed to protect workers constructing the Kansas Pacific Railroad from Indian attacks.

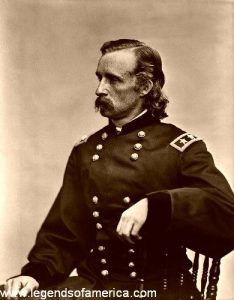

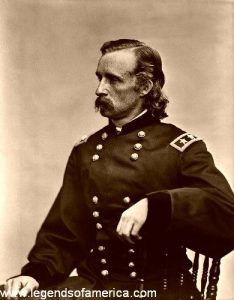

George A. Custer

In 1866 and 1867 Lieutenant George Armstrong Custer was stationed at the fort. Wild Bill Hickok was a scout for Fort Riley starting in 1867. On January 1, 1893, Fort Riley became the site of the Cavalry and Light Artillery School, which continued until 1943, when the Cavalry was disbanded. Several times throughout the years, the famous 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments of all-black soldiers, referred to as Buffalo Soldiers, were stationed at the fort.

Through both world wars and up until today, the post has remained active. The military reservation now covers more than 100,000 acres and has a daytime population of nearly 25,000, which includes the 1st Infantry Division, nicknamed the Big Red One.

Fort Riley is located on the north bank of the Kansas River three miles north of Junction City.

Contact Information:

Fort Riley Museum Division

785-239-2737

Fort Riley Hauntings

Artillery Parade Field – It is said that a woman wrapped in chains has often been seen walking across the field on clear nights. Who this woman was and what she might have done wrong in order to wind up in chains has never been known.

Camp Funston – Camp Funston was the largest of 16 divisional cantonment (temporary or semi-permanent military quarters) training camps constructed during World War I. Designated to be located at Fort Riley due to its central location in the nation, construction began on July 1, 1917, and the camp was completed on December 1st of the same year. With a capacity of over 50,000, it drew trainees from all over the Great Plains states. However, not long after the camp was completed and filled with soldiers, the 1918 flu epidemic, called the “Influenza Pandemic of 1918” hit the camp. Worldwide, this fatal flu virus cited as the most devastating epidemic in recorded world history killed more people than did World War I, an estimated 20 to 40 million people, including some 675,000 Americans. A global disaster, the flu took its toll on Camp Funston and Fort Riley, like it did the rest of the world.

Camp Funston, Kansas, 1918

When the war was over in 1918, the camp, as well as the Army shrunk and by 1922, Camp Funston officially ceased to exist. Today, its many buildings now serve as temporary housing.

Though those WWI soldiers-in-training are long gone; seemingly, at least one of them has chosen to stay. First reported in the late 1960s, a ghostly soldier in World War I uniform has been seen in the area, continuing his patrol. The tale alleges that a Public Works employee first spied the ghostly figure while repairing downed electrical lines. In the midst of a snowstorm, he noticed a soldier, in a heavy wool overcoat and rifle over his shoulder, pacing back and forth near the site of the old World War I era gymnasium. After repairing the lines, he decided to share his thermos of hot coffee with the young man; however, when he approached the area where he had spied him, the soldier was gone. More perplexing was the snow-covered ground showed no sign of footprints. Many believe that this long-forgotten soldier is one of those who died during the 1918 flu pandemic.

Old Trooper Statue at Fort Riley, Kansas

Cavalry Parade Field – Allegedly, a group of spectral riders are often seen and/or heard galloping across Cavalry Parade Field. According to the tales, numerous people have first felt a low vibration and heard the sounds of distant thunder before seeing a troop of soldiers galloping across the parade grounds. The riders then slow at the intersection of Sheridan and Forsyth Avenues, where, after one rider dismounts, the rest of the troop wheels around and rides away.

The intersection where the riders stop is where Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer once lived. Though the original home where Custer lived burned down long ago, the house was in the vicinity of this intersection. Some believe that the original dwelling stood where Quarters 21 is now located.

In any event, this group of spectral riders is believed to be an escort for Custer, and the dismounting soldier is thought to be the Lieutenant himself.

Way back in 1867 when Custer was stationed at the fort, but off a military campaign, he got the news that cholera had broken out at the fort where his beloved wife Libby was waiting for him.

Fearing for her safety, he selected an escort of his finest horsemen, turned over the 7th Cavalry to another officer, and the men rode back to the fort as fast as the could. Though he arrived to find Libby in good health, Custer was later court-martialed for deserting his unit and was relieved of command for one year. Perhaps this emotionally charged event has become a “place memory” haunting.

Interestingly, when these dark riders “appear” upon the parade grounds, different people sense them in different ways.

Some witnesses both see and hear the troops, but even more report that they can either see them or hear them, but not both. Those that hear them often hear various sounds, including the sound of thundering hoofs, as well as voices and the metallic jingle that accompanies horsemen.

Custer House – What was formerly known as Quarters 24, this structure is one of four original buildings left from the original post and has been in continual use since it was built. Made from native limestone from the area, the building is structurally similar to the original set of officer’s quarters that George Armstrong Custer and his wife, Libby, lived in from 1866 to 1867. Alas, the actual building, located near the Custer House, that the Lieutenant lived in has long ago burned down. Today, Quarters 24 stands as a museum exhibiting life at the fort in the late 1860s.

Haunting reports from this house first began in 1855, when the fort was hit by a cholera epidemic that claimed many lives. Immediately, the ghostly spirits were blamed on those who had died of the horrible disease.

The Custer House at Fort Riley, Kansas

Specific reports include a sergeant who worked in the building in the 1970s who said that he often heard strange noises coming from the upstairs rooms, including what sounded like someone putting a boot on, then stamping his foot on the floor. These noises always came at a time when no one was in the upstairs rooms. The same sergeant also reported that a teddy bear in the children’s room kept moving around. Though he always placed it on the bed before leaving, he would arrive the next day to find it had been moved again, usually sitting atop a rocking horse in the room.

Another soldier who worked in the Custer House reported that she would often arrive in the morning to find a bed in an upstairs room that appeared to have been slept in. The same soldier also reported often having felt as she was being watched when she was in the museum.

Infantry Parade Field — Long ago this field was also used as a polo field. Today witnesses say that two polo-playing gentlemen continue to be seen riding their horses and playing polo. Apparently, the two men are not polite if their game is interrupted. One soldier who had a personal experience was walking across the field one evening when he began to hear faint shouts and cheers from the distance. He then saw what looked like two figures playing polo. As he stopped to watch, the ball came near him and the two riders began to gallop toward him. When they neared, the soldier saw that one of the riders had no face, instead, there was nothing but a grinning skull. Obviously shocked, the man simply stared only to be surprised to hear the apparition yell, “Leave! Now, while you still can!” Panicked, the witness immediately ran from the field.

IACH (The Hospital) — In the Bio-Medical room, the fire alarm sounds frequently without being triggered. On one such occasion, after the alarm had gone off eight times, the fire marshal came and disconnected it; the alarm sounded three times after that.

Kansas Territorial Capitol – The first territorial capital was built in 1855 at the site of the now-extinct Pawnee City. Near the old capitol building is the Kaw River Nature and History Trail where the sorrowful voice of a woman can sometimes be heard drifting up from the banks of the river. One man, who often stopped to walk along the trail, tells of hearing the sounds of a woman singing a sad melody while walking along the path. Investigating, he moved closer to the river to investigate the source of the mournful voice. Upon arriving, he saw the shaded form of a flatboat or barge being pulled across the river by a dark, human-shaped form. When the apparition and the phantom boat reached the other side of the river, both simply vanished.

Most believe this may be the soul of a long-dead slave woman, who belonged to the man who owned the ferry in the 1850s. It is known that the ferry owner used a slave woman to pull the ferry back and forth across the river. Though this is the most likely explanation, might the spirit also be that of La Llorona, the weeping ghost who has long been known to haunt the rivers and waters of the American West?

Lower Parade Field – For many years people have reported seeing a lone rider who gallops madly across the field in the morning, only to disappear as quickly as he appeared.

Post Headquarters

Main Post — In this old building, people have often seen the ghostly figure of an old nurse.

NCO Club – Ghosts are said to haunt the doors of this club. An MP reported that a ghostly force jerked the door he was guarding open; the door was locked.

No. 1 Stable – For years soldiers on night duty have reported seeing a man in old-fashioned clothing ride through the stable and then disappear. Years later, when work was being done to the stable, the skeletons of horse and rider were found in an old ravine.

Post Cemetery — In the summer of 1855, a woman named Cornelia Armistead died of the cholera epidemic that was raging through the fort. Cornelia was the second wife of Major Lewis A. Armistead of the Sixth United States Infantry Regiment. As the cholera epidemic had already begun by July 1855, Armistead feared an outbreak among his troops and left Fort Riley, heading southwest. However, after traveling only nine miles, the disease took hold among his men and the unit was forced to stop. In the meantime, the epidemic was raging through Fort Riley, leaving in its wake as many as 125 men, women and children dead. On the very day that Major Armistead returned to the fort, his wife had died. A few years later, when the Civil War broke out, Armistead was killed in 1863. Since his death, Armistead has often been seen kneeling at his wife’s grave. Upset and weeping, his ghostly presence is wearing a dark blue uniform and clearly wishes to be left alone, if approached.

Quarters 124 – This house is reportedly haunted by a woman who drowned herself in a well on the fort grounds in the 1860s. Over the years, residents have reported hearing loud noises during the night such as someone dragging a wooden box up and down the stairs. At one point it was so bad that a priest was called in to do an exorcism. At first, the ceremony was successful, but apparently, the ghost returned several years later. However, nothing has been heard from the ghost recently.

Fort Riley Trolly Station Today

Trolley Station — In July of 1855 cholera was diagnosed at the fort and by the end of August, most of the Fort was dead. A woman named Susan Fox lived with her step-father in a small frame building across the creek from the trolley station. Engaged to be married soon, she was home alone for several days when her father was away and her fiancée in the nearby town of Pawnee City caring for the sick.

Contracting the horrible disease, she died alone in her home on August 30. Her finance discovered her body after he returned to the fort and she was buried in her wedding dress in a small grave near the railway bridge to the trolley station.

After her death, the residents of the house described many strange occurrences. Her fiancée was quoted as saying at the time “It was a difficult passage for her, and Susan came back to her old home several times demanding to be let in.”

Residents often reported hearing strange noises and shrieks. On another occasion, a maid ironing in front of a window was so frightened seeing Susan staring in at her that she threw the iron through the window.

The Post Commander, so irritated by the complaints and disturbances paid (out of Fort funds) for a priest from Junction City to perform an exorcism. Afterward, they razed the building to ensure Susan’s hauntings would stop. But, still, she is seen in many parts of the Fort, and especially around the trolley station, looking for something, or someone she lost.

These stories are but a fraction of the many haunting tales of Fort Riley. Each year the Historical and Archaeological Society of Fort Riley provides and Ghost Tour that tells the many tales of this historic, and apparently, extremely haunted post. Books are also available at the Fort Riley Museum that gives the details of these many apparitions.

On June 27, 1853, the camp’s name was changed to Fort Riley in honor of Major General Bennett C. Riley, who had led the first military escort along the Santa Fe Trail and had died earlier in the month.

The fort’s initial purpose was to protect the many pioneers and traders who were moving along the Oregon-California and Santa Fe Trails.

The First Territorial Capitol at Pawnee, Kansas was only used for one session, before moving to Lecompton, Kansas when the pro-slavery advocates were in control of the state. Photo by Kathy Weiser-Alexander.

Many of the buildings at the fort were built with the native limestone of the area, several of which continue to stand today. By 1855, the post was well-established and as more and more people moved westward, additional quarters, stables and administrative buildings were authorized to be built. In July, 56 mule teams arrived at the fort, loaded with materials and soldiers to expand the fort.

However, just a few short weeks later, cholera broke out among the fort and though the epidemic lasted only a few days, it left in its wake some 75-125 people dead.

As tensions and bloodshed increased between the pro and anti-slavery settlers, resulting in what has become known as “Bleeding Kansas,” Fort Riley’s troops took on the additional task of “policing” the troubled territory while continuing to patrol the Santa Fe Trail as Indian attacks increased.

When the Civil War broke out, the vast majority of the troops stationed at Fort Riley were sent eastward. However, some soldiers were left to continue to guard those traveling west and the base was utilized as a prisoner of war camp for captured Confederates. After the Civil War, troops from Fort Riley were needed to protect workers constructing the Kansas Pacific Railroad from Indian attacks.

George A. Custer

In 1866 and 1867 Lieutenant George Armstrong Custer was stationed at the fort. Wild Bill Hickok was a scout for Fort Riley starting in 1867. On January 1, 1893, Fort Riley became the site of the Cavalry and Light Artillery School, which continued until 1943, when the Cavalry was disbanded. Several times throughout the years, the famous 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments of all-black soldiers, referred to as Buffalo Soldiers, were stationed at the fort.

Through both world wars and up until today, the post has remained active. The military reservation now covers more than 100,000 acres and has a daytime population of nearly 25,000, which includes the 1st Infantry Division, nicknamed the Big Red One.

Fort Riley is located on the north bank of the Kansas River three miles north of Junction City.

Contact Information:

Fort Riley Museum Division

785-239-2737

Fort Riley Hauntings

Artillery Parade Field – It is said that a woman wrapped in chains has often been seen walking across the field on clear nights. Who this woman was and what she might have done wrong in order to wind up in chains has never been known.

Camp Funston – Camp Funston was the largest of 16 divisional cantonment (temporary or semi-permanent military quarters) training camps constructed during World War I. Designated to be located at Fort Riley due to its central location in the nation, construction began on July 1, 1917, and the camp was completed on December 1st of the same year. With a capacity of over 50,000, it drew trainees from all over the Great Plains states. However, not long after the camp was completed and filled with soldiers, the 1918 flu epidemic, called the “Influenza Pandemic of 1918” hit the camp. Worldwide, this fatal flu virus cited as the most devastating epidemic in recorded world history killed more people than did World War I, an estimated 20 to 40 million people, including some 675,000 Americans. A global disaster, the flu took its toll on Camp Funston and Fort Riley, like it did the rest of the world.

Camp Funston, Kansas, 1918

When the war was over in 1918, the camp, as well as the Army shrunk and by 1922, Camp Funston officially ceased to exist. Today, its many buildings now serve as temporary housing.

Though those WWI soldiers-in-training are long gone; seemingly, at least one of them has chosen to stay. First reported in the late 1960s, a ghostly soldier in World War I uniform has been seen in the area, continuing his patrol. The tale alleges that a Public Works employee first spied the ghostly figure while repairing downed electrical lines. In the midst of a snowstorm, he noticed a soldier, in a heavy wool overcoat and rifle over his shoulder, pacing back and forth near the site of the old World War I era gymnasium. After repairing the lines, he decided to share his thermos of hot coffee with the young man; however, when he approached the area where he had spied him, the soldier was gone. More perplexing was the snow-covered ground showed no sign of footprints. Many believe that this long-forgotten soldier is one of those who died during the 1918 flu pandemic.

Old Trooper Statue at Fort Riley, Kansas

Cavalry Parade Field – Allegedly, a group of spectral riders are often seen and/or heard galloping across Cavalry Parade Field. According to the tales, numerous people have first felt a low vibration and heard the sounds of distant thunder before seeing a troop of soldiers galloping across the parade grounds. The riders then slow at the intersection of Sheridan and Forsyth Avenues, where, after one rider dismounts, the rest of the troop wheels around and rides away.

The intersection where the riders stop is where Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer once lived. Though the original home where Custer lived burned down long ago, the house was in the vicinity of this intersection. Some believe that the original dwelling stood where Quarters 21 is now located.

In any event, this group of spectral riders is believed to be an escort for Custer, and the dismounting soldier is thought to be the Lieutenant himself.

Way back in 1867 when Custer was stationed at the fort, but off a military campaign, he got the news that cholera had broken out at the fort where his beloved wife Libby was waiting for him.

Fearing for her safety, he selected an escort of his finest horsemen, turned over the 7th Cavalry to another officer, and the men rode back to the fort as fast as the could. Though he arrived to find Libby in good health, Custer was later court-martialed for deserting his unit and was relieved of command for one year. Perhaps this emotionally charged event has become a “place memory” haunting.

Interestingly, when these dark riders “appear” upon the parade grounds, different people sense them in different ways.

Some witnesses both see and hear the troops, but even more report that they can either see them or hear them, but not both. Those that hear them often hear various sounds, including the sound of thundering hoofs, as well as voices and the metallic jingle that accompanies horsemen.

Haunting reports from this house first began in 1855, when the fort was hit by a cholera epidemic that claimed many lives. Immediately, the ghostly spirits were blamed on those who had died of the horrible disease.

The Custer House at Fort Riley, Kansas

Specific reports include a sergeant who worked in the building in the 1970s who said that he often heard strange noises coming from the upstairs rooms, including what sounded like someone putting a boot on, then stamping his foot on the floor. These noises always came at a time when no one was in the upstairs rooms. The same sergeant also reported that a teddy bear in the children’s room kept moving around. Though he always placed it on the bed before leaving, he would arrive the next day to find it had been moved again, usually sitting atop a rocking horse in the room.

Another soldier who worked in the Custer House reported that she would often arrive in the morning to find a bed in an upstairs room that appeared to have been slept in. The same soldier also reported often having felt as she was being watched when she was in the museum.

Infantry Parade Field — Long ago this field was also used as a polo field. Today witnesses say that two polo-playing gentlemen continue to be seen riding their horses and playing polo. Apparently, the two men are not polite if their game is interrupted. One soldier who had a personal experience was walking across the field one evening when he began to hear faint shouts and cheers from the distance. He then saw what looked like two figures playing polo. As he stopped to watch, the ball came near him and the two riders began to gallop toward him. When they neared, the soldier saw that one of the riders had no face, instead, there was nothing but a grinning skull. Obviously shocked, the man simply stared only to be surprised to hear the apparition yell, “Leave! Now, while you still can!” Panicked, the witness immediately ran from the field.

IACH (The Hospital) — In the Bio-Medical room, the fire alarm sounds frequently without being triggered. On one such occasion, after the alarm had gone off eight times, the fire marshal came and disconnected it; the alarm sounded three times after that.

Kansas Territorial Capitol – The first territorial capital was built in 1855 at the site of the now-extinct Pawnee City. Near the old capitol building is the Kaw River Nature and History Trail where the sorrowful voice of a woman can sometimes be heard drifting up from the banks of the river. One man, who often stopped to walk along the trail, tells of hearing the sounds of a woman singing a sad melody while walking along the path. Investigating, he moved closer to the river to investigate the source of the mournful voice. Upon arriving, he saw the shaded form of a flatboat or barge being pulled across the river by a dark, human-shaped form. When the apparition and the phantom boat reached the other side of the river, both simply vanished.

Most believe this may be the soul of a long-dead slave woman, who belonged to the man who owned the ferry in the 1850s. It is known that the ferry owner used a slave woman to pull the ferry back and forth across the river. Though this is the most likely explanation, might the spirit also be that of La Llorona, the weeping ghost who has long been known to haunt the rivers and waters of the American West?

Lower Parade Field – For many years people have reported seeing a lone rider who gallops madly across the field in the morning, only to disappear as quickly as he appeared.

Post Headquarters

Main Post — In this old building, people have often seen the ghostly figure of an old nurse.

NCO Club – Ghosts are said to haunt the doors of this club. An MP reported that a ghostly force jerked the door he was guarding open; the door was locked.

No. 1 Stable – For years soldiers on night duty have reported seeing a man in old-fashioned clothing ride through the stable and then disappear. Years later, when work was being done to the stable, the skeletons of horse and rider were found in an old ravine.

Post Cemetery — In the summer of 1855, a woman named Cornelia Armistead died of the cholera epidemic that was raging through the fort. Cornelia was the second wife of Major Lewis A. Armistead of the Sixth United States Infantry Regiment. As the cholera epidemic had already begun by July 1855, Armistead feared an outbreak among his troops and left Fort Riley, heading southwest. However, after traveling only nine miles, the disease took hold among his men and the unit was forced to stop. In the meantime, the epidemic was raging through Fort Riley, leaving in its wake as many as 125 men, women and children dead. On the very day that Major Armistead returned to the fort, his wife had died. A few years later, when the Civil War broke out, Armistead was killed in 1863. Since his death, Armistead has often been seen kneeling at his wife’s grave. Upset and weeping, his ghostly presence is wearing a dark blue uniform and clearly wishes to be left alone, if approached.

Quarters 124 – This house is reportedly haunted by a woman who drowned herself in a well on the fort grounds in the 1860s. Over the years, residents have reported hearing loud noises during the night such as someone dragging a wooden box up and down the stairs. At one point it was so bad that a priest was called in to do an exorcism. At first, the ceremony was successful, but apparently, the ghost returned several years later. However, nothing has been heard from the ghost recently.

Fort Riley Trolly Station Today

Trolley Station — In July of 1855 cholera was diagnosed at the fort and by the end of August, most of the Fort was dead. A woman named Susan Fox lived with her step-father in a small frame building across the creek from the trolley station. Engaged to be married soon, she was home alone for several days when her father was away and her fiancée in the nearby town of Pawnee City caring for the sick.

Contracting the horrible disease, she died alone in her home on August 30. Her finance discovered her body after he returned to the fort and she was buried in her wedding dress in a small grave near the railway bridge to the trolley station.

After her death, the residents of the house described many strange occurrences. Her fiancée was quoted as saying at the time “It was a difficult passage for her, and Susan came back to her old home several times demanding to be let in.”

Residents often reported hearing strange noises and shrieks. On another occasion, a maid ironing in front of a window was so frightened seeing Susan staring in at her that she threw the iron through the window.

The Post Commander, so irritated by the complaints and disturbances paid (out of Fort funds) for a priest from Junction City to perform an exorcism. Afterward, they razed the building to ensure Susan’s hauntings would stop. But, still, she is seen in many parts of the Fort, and especially around the trolley station, looking for something, or someone she lost.

These stories are but a fraction of the many haunting tales of Fort Riley. Each year the Historical and Archaeological Society of Fort Riley provides and Ghost Tour that tells the many tales of this historic, and apparently, extremely haunted post. Books are also available at the Fort Riley Museum that gives the details of these many apparitions.